- Fingers

- Posts

- Boomers vs. BeatBox

Boomers vs. BeatBox

Plus: Back before lobbying devoured DC!

Editor’s note: The column below was originally published on February 2nd, 2023, back when Fingers was much smaller. Following the Wall Street Journal’s report Tuesday that Anheuser-Busch InBev is soon to acquire BeatBox for $700 million—a scoop that I was also chasing, ah well—I’m revisiting this piece about the implications of the Tetra-Pak’d riot punch brand’s success for the broader US wine industry. (See also: this, this, and this.) This piece is nearly three years old, so the sales data aren’t current, but they’re still directionally useful; overall, I’m pretty pleased with how this take has held up! Hope you enjoy—Dave.

Every year for the last two decades, an executive at Silicon Valley Bank named Rob McMillan has published a report called “State of the U.S. Wine Industry.” It’s a massive document filled with research and polling and sales data about the business of American wine, and insiders and analysts alike consider it bellwether on how things are going, oenologically speaking. As it has been for the past several years, the 2022 edition painted a pretty dire picture for the future of the U.S. wine industry.1 Aside from the standard headwinds, the biggest, most intractable problem McMillan2 sees for the category—and particularly its volume-driving sub-$15, “starter” bottle segment—is one you could probably guess even if you’ve never read a page of the SVB report.

Namely, old people drink a lot of wine, and young people don’t, and the former is apt to die a lot sooner than the latter. I swear that’s only slightly more crass than McMillan, a boomer himself, puts it (emphasis mine):

The median boomers are now on the other side of their normal retirement age of 66, and the spend in that cohort will have to decline unless they somehow get a reprieve from death and taxes.

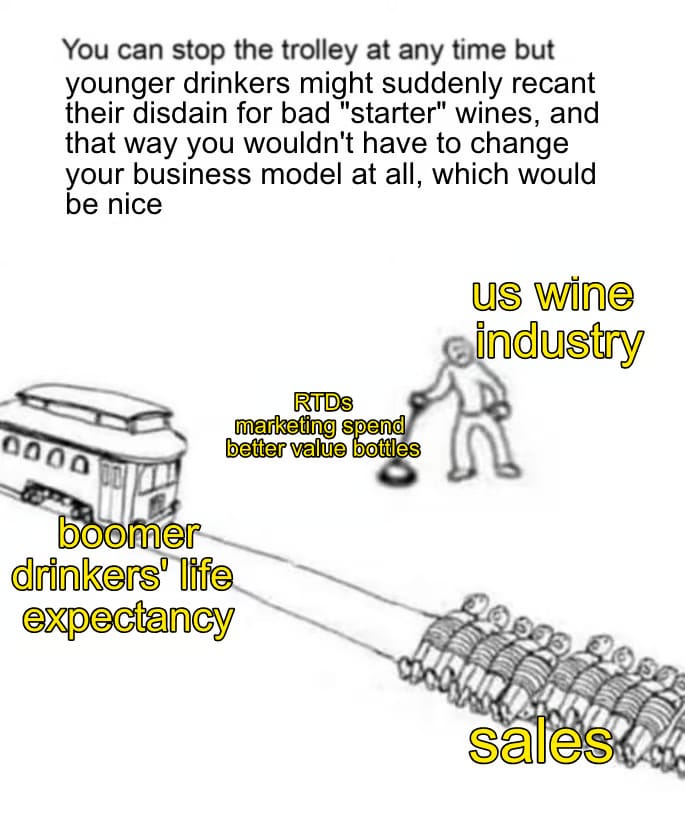

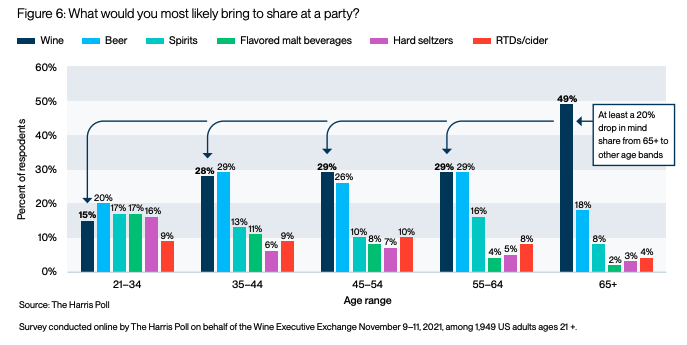

Rob’s got jokes! About the inexorable march towards death that characterizes the human condition! A man after this boozeletter’s heart, he is. Anyway, being as how I know way less than wine than spirits or beer, I spent some time with this year’s 102-page report this past week. It’s a very thorough document, with colorful charts screaming “the kids may be alright, but wine sure the fuck isn’t!” from a variety of different angles. Like this one, which shows that younger millennial/Gen Z drinkers are more likely to bring White Claw to a party than white Zin:

Okay, I’m editorializing slightly, but you get the point. If you’re interested in the American wine business, I recommend reading all of McMillan’s 2022 dispatch in full, or at least skimming it while ignoring everyone on your next Zoom. It’s great! But once I was about halfway through it, I started getting a nagging feeling that something was missing. A little CMD+F-ing confirmed that neither “BeatBox” nor “BuzzBallz” appeared even once in the entire report.3 With respect to Mister McMillan,4 omitting these rapidly growing wine-based brands from an industry report sounding the alarm on younger drinkers’ apparent lack of interest in wine feels like a missed opportunity. Here’s why.

Even though BeatBox and BuzzBallz have been two of the hotter wine-based ready-to-drink brands on the market for a few years now, I see very few wine companies following their lead or even cherry-picking strategies from either. Specifically their single-serve packages, which overindex in popularity amongst younger drinkers. Single-serve wine has been a thing for a while, with brands from Wolffer Estate to Dark Horse canning product in hopes of fitting wine into more “occasions.”5 And that’s all well and good, says McMillan, but:

The ready-to-drink (RTD) beverage segment is another potential on-ramp for new consumers, but apart from wine in cans (which can be considered an RTD), the wine industry barely participates in the category despite the fact that shelter-in-place mandates helped RTD beverages explode.

Right! Exactly! Drinkers may not realize this, but just like malt-based hard seltzers that taste nothing like beer, you can make wine-based alcoholic beverages that don’t taste anything like wine. If you’ve ever seen premixed cocktail cans/bottles/pouches/etc. in a store that doesn’t sell any other type of full-proof liquor, there’s a good chance that’s a wine-based product. And if it comes in a cute lil’ vessell that looks like a water balloon with a pop top, it’s a BuzzBallz Chiller.

Though the naturally flavored orange wine “cocktails” may be an affront to winemakers accustomed to pitching their products on the merits of terroir, provenance, vintage, etc., the simple fact is BuzzBallz sells a shitload of wine. It ships over a million cases a year; in 2020, it did nearly $70 million in revenue.6 The brand is popular with Gen Z drinkers as much for its approachable flavors as for its photogenic packaging. As Drew Millard reported for Vice a couple years ago, “these little orbs of intoxication… have become something of a meme on TikTok,” a platform that even old-school wineries have realized drives purchasing intent amongst younger customers.

If BuzzBallz is an affront to American winemakers, BeatBox, with its fruity flavors and Bang-banged-a-Bota Box aesthetics, might be a flat-out abomination. Launched in 2011, the wine-based party punch picked up an investor in Mark Cuban after a successful Shark Tank appearance in 2014, and has since gone absolutely gangbusters. In October 2022, BeatBox closed a $15 million raise at a valuation of $200 million; in December, Brewbound’s Jess Infante reported it had doubled in volume since last year, racking up $40 million in revenue. Like BuzzBallz, the brand is optimized for social-media cameos and growing like a weed in the single-serve RTD space—both crucial factors for courting younger drinkers that American wine companies have struggled with.

I feel for winemakers, I really do. It looks like the category’s best days are behind it (on American shores, at least), and I can’t imagine many of them got into the business to make flavored wine drank for the TikTok set. BuzzBallz and BeatBox represent an extreme/maybe-unpalatable end of wine's innovation spectrum, but it’s the extremely successful end where a lot of the growth is right now. Are they on-ramps to higher-end “premium” wines (sales of which are doing just fine per SVB’s report)? Absolutely not. But if the crisis is as urgent and existential as McMillan argues it is, and convincing American drinkers to spend a little more per-bottle to buy better wine is a longer-term initiative,7 producers need to be thinking about short-term survival. To survive below $15, American winemakers can either start "mak[ing] better fucking everyday wine and sell[ing] it for a reasonable fucking price,” as Jason Wilson of the Everyday Drinking newsletter suggests; or rethink how their product can fit into a changing market8 using upstart wine-based brands’ undeniable growth as a guide. Or a little of both!

Those that do neither… I mean, the outlook sounds grim. Don’t take it from me, take it from one of the more depressing passages in McMillan’s 2022’s report:

[W]hatever we’ve collectively tried to do to engage with the younger consumer in the last decade hasn’t been good enough. In fact, if we are doing something, the results are getting worse, so you could argue that we should immediately stop doing it.

Here’s hoping the “State of the U.S. Wine Industry” bears better news next year.

🤝 Consider upgrading to a paid subscription!

This edition of Fingers is free to read in full. Most are not. If you enjoyed this column, you’ll may also like:

Upgrade your subscription now to read those pieces, and all of boozeletter’s award-winning, independent coverage and commentary:

Fingers is 100% reader-supported and AI-free. Your paid subscription directly funds independent journalism about drinking in America. Hope to see you on the other side of the paywall.—Dave.

📬 Good post alert

If you see a good post that the Fingers Fam should know about, please send me that good post via email, or a DM on Bluesky or Instagram.

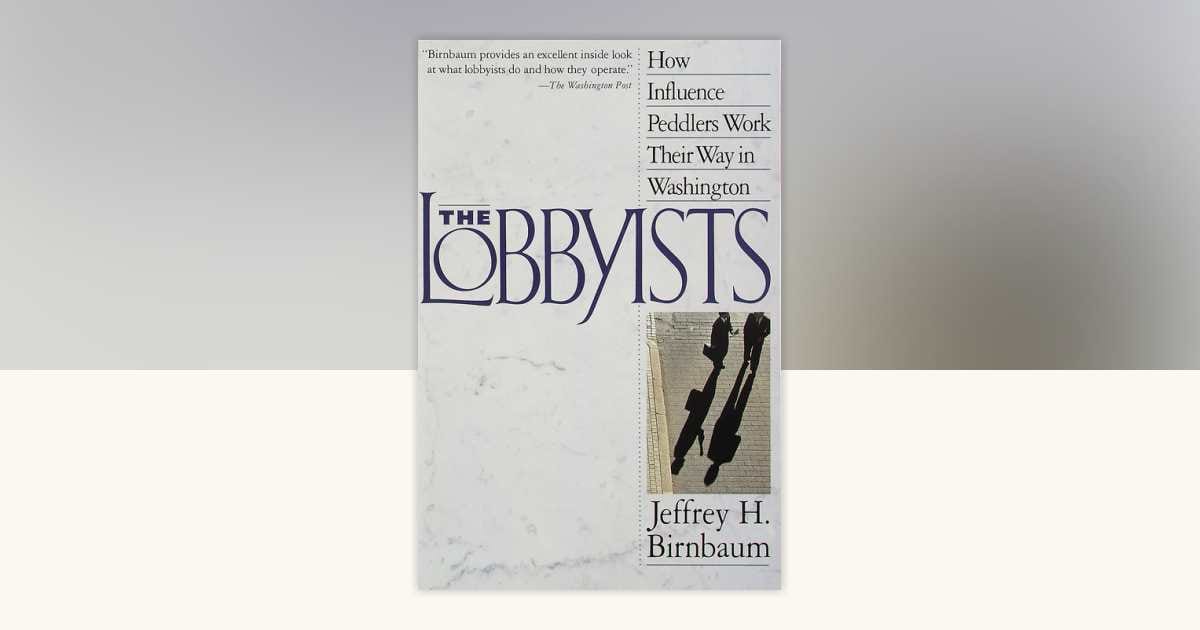

📚 Back before lobbying devoured DC

Welcome to Boozeletter Book Reviews, spotlighting new-to-me volumes relevant to the business and culture of drinking in America. Please consider purchasing your books via The Fingers Reading Room to support the boozeletter, thank you.

How many members of Congress have a strong opinion about, say, hemp-derived THC, do you think? How many of them even know what it is? Whatever the number is, it’s not 100%. Federal lawmakers, preoccupied as they are with courting donors to ensure their perpetual reelection, don’t have time to become experts on every issue before Congress, and their staffs are neither large nor well-paid enough to pick up the slack.

Virtually since the creation of the United States, lobbyists have stepped into this breach, proffering specialized expertise in exchange for an opportunity to advance their clients’ specialized interests. But starting in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, wrote longtime Beltway journalist Jeffrey H. Birnbaum in his 1992 book, The Lobbyists: How Influence Peddlers Work Their Way in Washington, backroom wheeling-and-dealing in Washington DC took on a much more formal, tactical, and professional bent. Aided by then-new technology, ever-increasing amounts of cash, and a pre-Abramoff low profile in the public consciousness, operatives from both Republican and Democratic lobbying shops revolutionized the greasy business of buttonholing “MoCs”—“members of Congress,” in the jargon—on behalf of deep-pocketed trade organizations and major corporations. Sometimes even less-deep-pocketed labor unions and nonprofit groups, too! But less often.

Lobbyists is a detailed, juicy, not-totally unsympathetic look at the how the sausage got made in a simpler (albeit still pretty complicated and cynical) era in the nation’s swamp. The Capitol-steps influence-peddling of three decades past pales in comparison to the hustling in/around the utterly craven and captured Congress of today, of course. But if you want to understand how we got here, you’d do well to start there. 8.5/10.

Don’t miss out, follow Fingers on Instagram today. It’s free and your feed will thank you. (Not really, that would be weird. But you know what I mean.)

1 According to the National Association of American Wineries, directly employs roughly a million full-time equivalent workers, which is WAY more than I would’ve guessed.

2 But not everybody! Journalist Jason Wilson of the Everyday Drinking newsletter argues that the problem is actually much simpler, and has nothing to do with marketing or aging demographics. “If wine has an ‘old people problem’ it’s simply because old people still buy the industry’s starter wines,” rather than graduating up to higher qualities at slightly higher pricepoints. For what it’s worth, I don’t see that explanation as mutually exclusive from winemakers getting savvier about marketing, packaging, etc.

3 Shoutout to Good Beer Hunting Sightlines editor and Friend of Fingers Bryan Roth, who realized roughly the same thing at roughly the same time.

4 And I guess!!! to Eric Asimov, the New York Times’ longtime wine critic, who wrote up the report without mentioning BeatBox or BuzzBallz, either.

5 This is how the bev-alc industry types talk about the various times and contexts in which people drink. A pool party is a common “occasion;” your child’s Saturday morning soccer game, while less common and socially acceptable, is also technically an occasion.

6 The brand also makes spirits-based cocktails these days, so not all of this is wine. But still.

7 McMillan is sometimes criticized for being a Chicken Little about the American wine business’ appeal with younger drinkers, but to his credit, he’s tried to get more hands-on on this front in particular… with mixed results.

8 Under a different brand name, even. No need to sully your traditional flagship with the vagaries of the c-store. Look at Sazerac: the maker of Pappy Van Winkle, one of the most coveted bourbons on this green earth, absolutely banks bucks off Fireball and a malt-based version of Fireball, and nobody gives a shit! (Except maybe a federal jury; TBD!)

Reply